Everyone loves a good bad guy, and no one more than documentary filmmaker Billy Corben. And notorious cocaine cartel hitman Rivi Ayala – with his charisma and utter amorality, his perfect recall of each time he gunned someone down in Miami’s streets – is a really good bad guy.

“He’s a fascinating, fascinating character,” says Corben, who put Ayala at the center of the Cocaine Cowboys films, the cult documentaries he and partner Alfred Spellman made about Miami’s cocaine wars of the 70’s and 80’s. “He’s had a life full of conflict and drama. He’s full of contradictions.”

Just like Miami. Which is why Miami New Drama is staging Confessions of a Cocaine Cowboy, based on Ayala’s confessions in extensive depositions and interviews. With previews starting Thursday, the play may be the most ambitious effort yet in the troupe’s mission to tell the stories of the city. Call it theater as civic psychotherapy. Miami New Drama’s version of Ayala’s tale goes to the heart of our traumatized fascination with Miami’s most notorious era; when warring drug cartels filled Miami with cocaine, cash and previously unimaginable violence, as shootouts in streets and shopping malls made us the deadliest city in America.

And one of the most famous. As the Cocaine Cowboys films showed, the era erased the moribund glamour of the 50’s and 60’s, replacing it with a darkly seductive, anything-can-happen-here decadence – Scarface, Miami Vice. It’s an image that, despite our supposedly grown-up glitz, we still wear with a knowing, “this is Miami” swagger. We’re different and we know it.

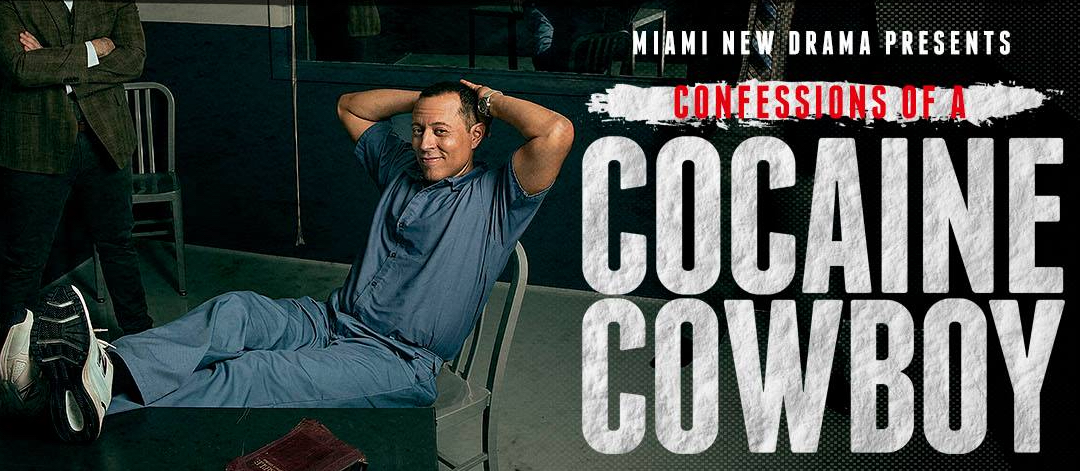

Yancey Arias as hitman Rivi Ayala and Zilah Mendoza as drug queenpin Griselda Blanco

“These stories are a kind of twisted love letter to our hometown that is recognized the world over,” says Corben. “For Miami… there’s a certain pride that we survived the craziness. This is our reputation.”

“Rarely does a piece of art change the narrative of a city,” says Miami New Drama artistic director Michel Hausmann, who is directing Cocaine Cowboy. “We all thought we knew what Miami was. Then Billy came along.”

The two men became good friends soon after Hausmann launched the troupe at the Colony Theatre on Lincoln Road in 2016, where Corben’s rakontur productions has offices. They bonded over happy hours and hours of talk about a city – and a mission – that obsesses them both.

“What binds us is we believe in using our art, our medium to change society,” says Hausmann. “We’re extremely centered on our community, on Miami. Inevitably we clicked.”

The play depicts two cops interrogating Ayala, played by Broadway and TV standout Yancey Arias (Thief, the title role in Kingpin), flashing back to contradictory accounts of Ayala’s past as hitman for infamous drug queenpin Griselda Blanco (Zilah Mendoza.) The structure incorporates dominant contemporary dramatic themes: charismatic anti-hero, true crime drama, dueling versions of the truth.

Corben and his partners spent years trying to turn Ayala’s life into a TV series. Hausmann tapped into Corben’s frustration with that effort, and his roots studying theater at New World School of the Arts.

“Michel cracked the code – if you want anything done right you have to write it yourself,” Corben says. “It’s very difficult to direct someone to write what’s in your head.”

Or to explain Miami’s multi-cultural immigrant tribalism, or crucial factors like the rivalries between Colombian and Cuban cartels, to LA producers whose idea of Hispanics is an indeterminate Mexican cliche. (The actors in Confessions come from multiple Latin American cultural backgrounds.)

“Miami is a unique environment,” Corben says. “It’s not a melting pot. Most people don’t understand an environment rich with diverse Hispanic culture.”

“As Rivi says in the play, don’t get into a road rage fight in Miami until you see what flag they’re flying. ”

To work with Corben on his first play, Hausmann enlisted playwright Aurin Squire, another Miami native who brings a different set of skills and understanding to the project. The two collaborators are almost the same age – Corben is 40, Squire 39. But the trickledown effect of the drug wars that Corben saw growing up in North Miami Beach was mostly benign: new cars and renovated homes. Whereas Squire, who grew up in Opa-Locka (still one of the most dangerous cities in America), heard gunshots and saw murder victims floating in the canal.

“As a child you don’t take it in because that’s your normal,” Squire says. “It’s only when you go somewhere else that you realize that’s not how it has to be.”

He realized something else after seeing the Cocaine Cowboys film around 2013. “This is the eagle eye view of what I was seeing – small time drug dealers shooting each other,” Squire says. “When you’re in the Cali or Medellin cartel, you see the whole flow chart. I was at the bottom of the flow chart. But these guys in Cali were responsible for a lot of what happened in my community.”

Squire got out as soon as he could, studying journalism at Northwestern University, writing for the likes of the Chicago Tribune and The New Republic before switching to theater, attending the Juilliard School and going on to residencies and productions at major theaters including London’s Royal Court Theatre, Lincoln Center Lab, and National Black Theatre. He wrote for the TV hit This Is Us and is a writer/producer on CBS’s The Good Fight.

Miami still resonates in Squire – his plays about Opa-Locka got him into Juilliard. But despite his success, he’d never had a play produced here until Hausmann approached him.

“It’s a full circle moment,” Squire says. “I grew up in an area plagued by drugs and violence, where you can’t wait to get away. But you grow up and your hometown does too. When you look back it’s that mix of feelings, the tragedy but also the triumph… You can do whatever you want, make yourself whatever you want.”

The show’s creators draw parallels between the contradictions of the cocaine era and the present that will take the play beyond perverse nostalgia. Our morally ambivalent fascination with swaggering real and fictional bad guys – Al Capone, The Godfather, Scarface, The Sopranos, narcocorridos, Breaking Bad, Queen of the South telenovelas. The economic rocket boost that billions in drug cash brought to everyone from bankers and developers to cocktail waitresses and guys offloading planes – and the international money washing through the luxury condo towers transforming the city yet again. The senseless horror of children dying in drug shootouts – or school massacres.

“We do explore through the violence in the show the very real fears all of us have nowadays about leaving our homes or sending our children into the world,” Corben says.

There are, of course, still plenty of concrete connections to the world of Cocaine Cowboy. Some of the people depicted in the play are coming on opening night. Last December Squire was waiting for his breakfast in a Miami Beach restaurant, when the guy nursing a Bloody Mary next to him struck up a conversation, and asked what he was doing. Working on a show about the 80’s cocaine wars, Squire replied.

“I used to smuggle cocaine!” the guy said. “Well,” Squire told him, “you should come see our play.”

Previews of Confessions of a Cocaine Cowboy are March 7 to 15; the play opens March 16 and runs through April 7, at the Colony Theatre, 1040 Lincoln Road, Miami Beach. Tickets are $39 to $79 ($150 for opening night), at www.colony.org or 305-674-1040.